Originally published at MintPress News.

AUSTIN, Texas — On May 19, about two dozen disabled Texans and their personal care aides gathered at the entrance to the governor’s office chanting: “Greg Abbott, come on out! We’ve got something to talk about!” Others were inside, refusing to leave. They’d come from around the state to demand better wages for personal care attendants, the helpers on whom their independence depends.

The disabled activists at the governor’s office represented ADAPT of Texas, and the aides were from an ADAPT subgroup, Personal Attendant Coalition of Texas (PACT). At issue in Texas are the wages for a type of aide known as community attendants, who are not hired by home care services that are paid by private insurance. Instead, community attendants’ wages are paid through federal Medicaid dollars and the Texas General Revenue fund.

At the time of the protest, the base wage for community attendants was $7.86 per hour, just slightly higher than the state minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. By comparison, the city of Austin enforces a living hourly wage of $11 for city employees and at construction projects supported by tax incentives.

Personal care aides typically work with the disabled between one and several times daily and help the disabled accomplish everyday tasks.

“My attendant comes in the morning, helps me get dressed and ready to go, and then prepares a meal,” Danny Saenz, an ADAPT activist at the protest, told MintPress News. “They’re very important.”

Without his attendants, Saenz, who lives in an apartment of his own, would have to move back in with his aging mother. For many of the nation’s disabled and elderly, these aides are the only thing separating them from life in a nursing home and an independent existence in their communities.

A factsheet provided by ADAPT suggests that at $8.51 per hour, Texas’ average wages for aides are the lowest in the nation– lower even than other conservative states like Arizona, which ranked 28th, with an average attendant wage of $10 per hour, and Florida, which ranked 30th, with an average attendant wage of $9.82 per hour. At wages this low, few people are eager to enter into the profession at all, and those who do can be lured to other industries, like fast food, that pay better.

“In our community, people aren’t able to find attendants,” Cathy Cranston, an Austin-based PACT organizer, told MintPress. “We don’t have a competitive wage at all when someone can go to Wal-Mart or Target now and start at $10 hour.”

Protesters at the governor’s office were demanding base wages of $10 hour and a special legislative session to address what they called “the crisis facing the community attendant workforce, including wages and recruitment and retention.”

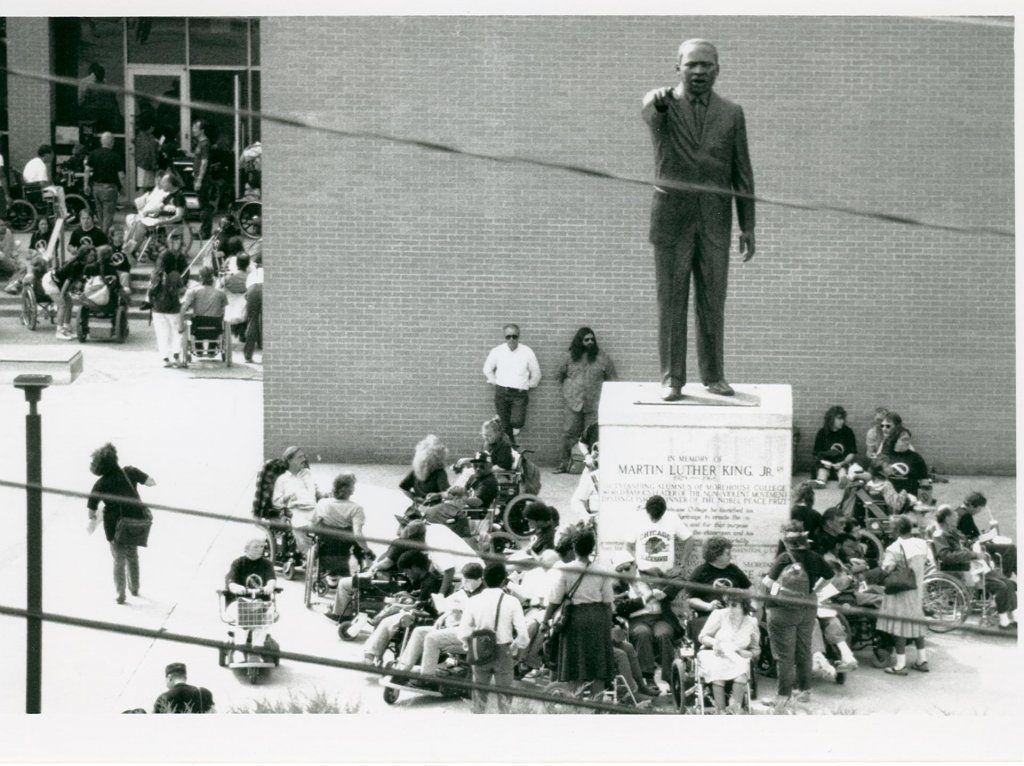

Around the governor’s reception area, Texas state troopers stood nervously with their arms folded, listening to the protesters’ chants echo throughout the Capitol’s marble halls. The troopers ensured that traffic continued to flow into and out of the office, but otherwise made no attempt to interfere or encourage the protesters to leave. They knew better — ADAPT members’ wheelchairs were loaded with water, food, and even sleeping bags, and, more importantly, they represent a tradition of direct action and holding space that goes back decades.

A history of direct action

Originally founded in Denver in 1974, the group adopted the acronym ADAPT — which originally stood for Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transit — because of an initial focus on demanding wheelchair accessible bus lifts on public transportation. A plaque at a Denver intersection marks the site of the first public demonstration for accessible transportation, where on July 5 and 6, 1978, 19 members of the original group blocked a bus and other traffic while chanting, “We will ride!” This early protest triggered a nationwide disability-rights movement that eventually led to the adoption of lifts on almost all public transportation today, revolutionizing the lives of millions of disabled Americans.

Over the years, the acronym ADAPT became more of a generic battle cry as the group’s focus expanded beyond public transportation to other issues of access. In addition to the national chapter, almost two dozen states now have chapters focusing on local issues, though their members often travel to assist national actions in Washington, D.C., where their ability to disrupt business at government buildings is so notorious that their marches are trailed by dozens of police and Homeland Security vehicles. On these Washington trips, ADAPT activists eat McDonald’s food — a link to another historic action in which members blockaded one of the fast food chain’s restaurants and, according to group lore, the chain opted to demolish the restaurant rather than make accessibility modifications.

Despite their reputation for effective direct action, it’s ADAPT’s last resort after using every other tool available. ADAPT of Texas began their latest campaign for better attendant wages with meetings with gubernatorial candidate Greg Abbott in 2014. They continued voicing their demands throughout the 2015 legislative session, which began on Jan. 13 and ended June 1. The Texas Legislature meets for only 140 calendar days every odd-numbered year, leaving citizens, activists and lobbyists scrambling to get their issues heard in just a few months, unless the governor calls for a special session.

“We educated legislators, we visited every week, two to three times a week. We went to the hearings,” Cranston told MintPress. “They got the message, they just didn’t have the will. So we were there at the governor’s to ask him to put pressure on the legislators.”

Women suffer the most under poverty wages for attendants

Outside the governor’s office in May, MintPress spoke with Carrie Warner, an activist with PACT, who has worked as an aide for two decades in Austin. The work has taken its toll on her — while she used to seek additional part-time jobs like catering, she now suffers from repetitive motion syndrome caused by her attendant work. Warner says she’s more dependent than ever on her limited wages, as her ability to seek other work decreases with age.

Warner explained the difference a base wage of $10 an hour would make in her life: “I wouldn’t wake up every day and wonder how I’m going to make ends meet.”

In many ways, Warner’s struggle is symbolic of the overall crisis facing personal care attendants. Low wages make it harder to attract new workers, and meanwhile the workforce is aging.

“Both of my attendants are over 60,” Danny Saenz told MintPress. “A lot of attendants are on medical assistance programs, some of them even qualify for Medicaid or were lucky enough to serve our country and have the VA to fall back on. Otherwise, they can’t afford any health care.”

“I’ve been doing this now for about 30 years,” said Cranston, “and I’m 55. Most of our workers are women, and we’re all aging out, no one is going into this profession.”

According to data assembled by the AARP Public Policy Institute in 2007, the average age of a caregiver was 46. And the workforce is overwhelmingly female.

“Almost 90 percent of nursing, psychiatric, and home care aides, the frontline workers in both institutional and home- and community-based settings, are women,” according to the AARP.

As the population’s average age rises, more Americans will need living assistance, and few will want to live in nursing homes. And, thanks to their longer average lifespan, that means more women than ever will need aides, in a profession where the AARP estimates that two-thirds of home care recipients are already women.

Warner suggested that attendants are devalued, like other forms of labor perceived to be “women’s work.”

“I believe the work is less appreciated,” she said. “The attitude is, ‘Oh well, women always take care of everyone.’ It’s expected. And maybe they think, ‘Well, they’ve survived this long, they can still do it.’”

A 14-cent raise is not enough

The Texas Capitol closes at 10:00 p.m., but 15 members of ADAPT and PACT refused to leave at the end of that day in May. After being temporarily detained by state troopers, they were cited with misdemeanor criminal trespass and told to appear in court in July.

Meanwhile, the session ended with only a tiny improvement for community attendants’ lives. Abbott’s 2015 state budget proposed raising community attendant’s base wages to $8.26 an hour, but the Legislature could only agree to a 14-cent raise, bringing hourly base wages to an even $8.

“At $8 per hour, there is no money for health insurance, vacation or sick leave,” Bob Kafka, an ADAPT organizer, told the Houston Chronicle after the protest.

Cranston concurred in her conversation with MintPress: “That 14 cents won’t even buy an Austin bus pass.”

There was one other piece of good news for the disabled and their attendants. Cranston told MintPress that, under pressure from groups like ADAPT and PACT, legislators added a rider to House Bill 1, the omnibus state budget bill, that would encourage the Texas Health and Human Services commission to use some of its budget to “create strategies for recruitment and retention for the projected number of attendants that will be needed in the future.”

Cranston says ADAPT and PACT will work to make sure the commission follows through on this directive, and they’ll continue to pressure legislators for higher wages during the year-and-a-half gap between sessions.

“As an advocacy organization, we can use that rider. But even though they’re supposed to do it, it doesn’t mean they will,” she concluded. “Activists have to be ever vigilant to make sure the people in politics are accountable.”