Originally published at MintPress News.

AUSTIN, Texas — Many have suspected through the years that extreme stress and trauma leave their mark not just on their victims, but on their descendants as well. Now science is catching up to these beliefs through the developing field of epigenetics.

Epigenetics is the study of how environmental factors can change the expression of a person’s DNA, often in ways which are inheritable by the next generation. This science looks at not just which genes are in a person’s DNA — the genetic “instruction manual” — but also how cells choose to read and interpret that instruction manual throughout a lifetime of development.

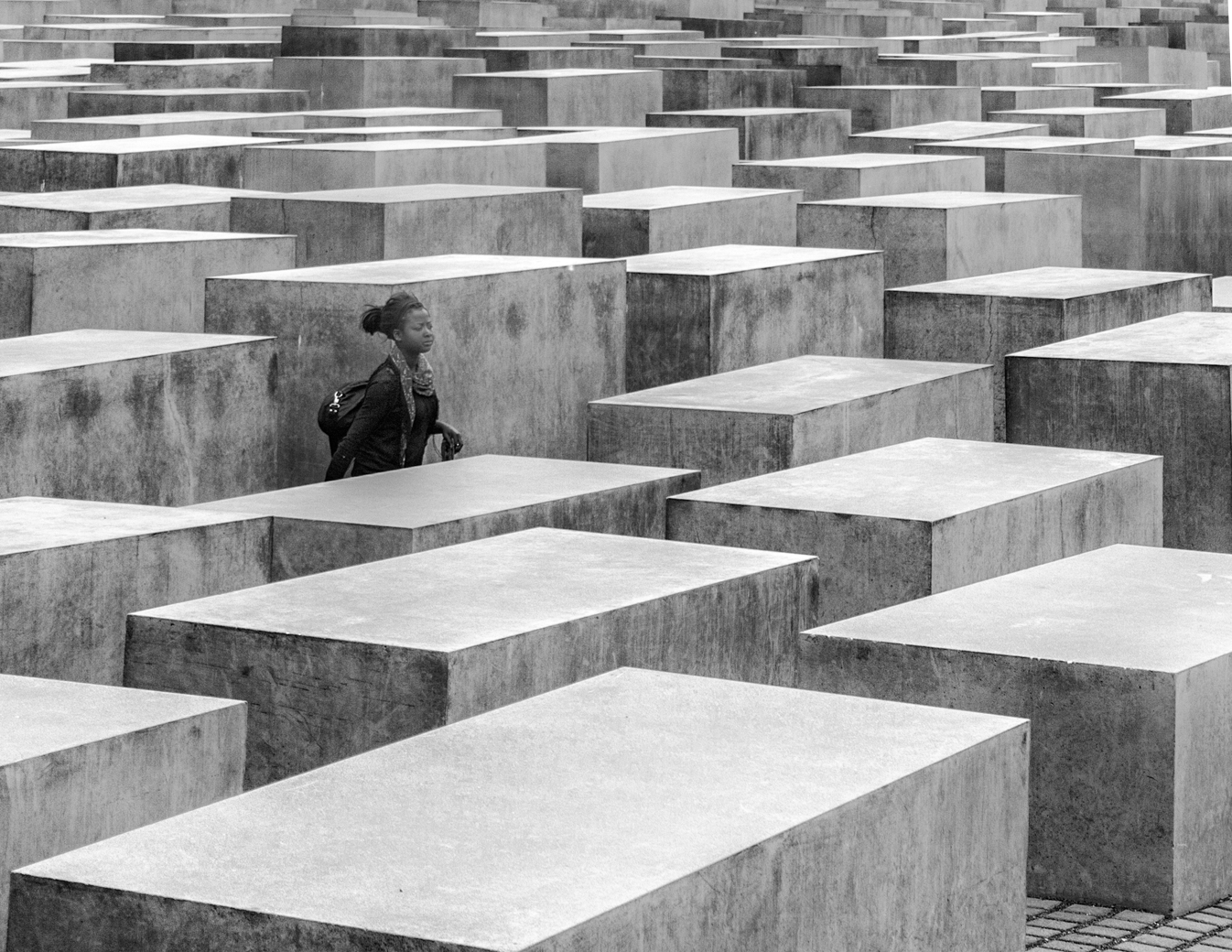

Earlier this month, Biological Psychiatry published a new study called “Holocaust exposure induced intergenerational effects on FKBP5 methylation,” in which the authors studied 32 Holocaust survivors and their adult children. All of the older generation of subjects had either been interned in concentration camps or otherwise intimately witnessed the torture and horror of Nazi genocide.

The authors refer to earlier research into hormones called glucocorticoids, which are released in times of high stress. Repeated exposure to the hormone can reduce a person’s ability to handle trauma by switching off certain genes which help manage stress. However, through examining the descendants of Holocaust survivors, this new study is the first to suggest that these changes can be transmitted to the next generation.

According to Helen Thomson, writing last week for The Guardian, the Biological Psychiatry study builds on earlier research supporting ways one generation’s environmental factors can affect their offspring:

For example, girls born to Dutch women who were pregnant during a severe famine at the end of the second world war had an above-average risk of developing schizophrenia. Likewise, another study has showed that men who smoked before puberty fathered heavier sons than those who smoked after.

Rather than coming as a surprise, these findings may confirm what survivors of trauma have long suspected to be true, noted Mary Annette Pember, a health journalist with Indian Country Today Media Network. Writing about epigenetics and an American Academy of Pediatrics study on the lasting effects of childhood trauma, she reported in May:

Folks in Indian country wonder what took science so long to catch up with traditional Native knowledge. “Native healers, medicine people and elders have always known this and it is common knowledge in Native oral traditions,” according to LeManuel “Lee” Bitsoi, Navajo, PhD Research Associate in Genetics at Harvard University during his presentation at the Gateway to Discovery conference in 2013.

Bitsoi suggested that epigenetic changes may be linked to “development of illnesses such as PTSD, depression and type 2 diabetes.” For America’s surviving Indigenous people, the effects are widespread:

According to researchers, high rates of addiction, suicide, mental illness, sexual violence and other ills among Native peoples might be, at least in part, influenced by historical trauma.

Another researcher, Bonnie Duran, an associate professor at the University of Washington, calls this a “colonial health deficit.”

Not only does this new study illuminate the long-term effects of the suffering of Holocaust survivors and Native Americans, but it also suggests an intriguing avenue for future research: whether victims of other historic or ongoing genocides, such as America’s black and brown population or the millions of those killed in U.S. wars in the Middle East, also suffer from a colonial health deficit.