Last time I was in college I took an anthropology course. It stands out as one of the most enjoyable and enlightening experiences I’ve had in a formal educational setting. This wasn’t a particularly progressive school (a community college in Bryan, Texas!) nor was the class an advanced one; it was your basic introduction to the topic. Yet what was so powerful about it was the way it made me feel about my polyamory and the other ways I diverge from cultural norms. There was no one in either of our textbooks practicing anything like the “V”-shaped relationship I was part of at the time, but if one took nothing else away from the course it was that humanity through the ages and around the world was almost infinitely diverse. We all have the same basic drives to eat, sleep, connect intimately and sexually, build families, and yet we form fulfill them in almost limitless ways. In that light, my own divergent choices couldn’t stand out so much.

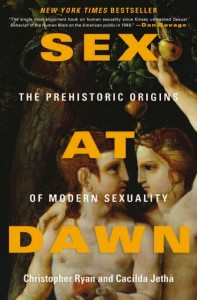

Reading Sex At Dawn, the 2010 book by psychologist Christopher Ryan and psychiatrist Cacilda Jethá brought this feeling back, stronger than ever. My friend Kiki called it the most important book on polyamory she’d ever read and, though the book is not specifically geared toward us, I totally understand her perspective. With one notable exception (which I’ll get into later), this went beyond simply making me feel like one part of a diverse tapestry: it actually made me feel like my choices and behavior might actually be normal when compared against the entirety of human existence.

The standard narrative of human relationships is that monogamy and marriage are ancient practices, perhaps dating back to the origin of the species. Both religion and culture insist that we began as married couples in one form or another, and science has worked hard to prove this as our “natural” state, with science journalists often announcing the latest discovery about neurological or genetic imbalances which make a person stray from this norm. Marriage, we are told, is the oldest arrangement between man and woman, where he agrees to protect her and raise their children in return for the sexual favors she gives him. Monogamy is necessary for her protection and so he knows that he’s not wasting his resources raising another man’s child.

Polyamorists sometimes respond to this narrative by arguing that in our modern times none of this is necessary any more. we are now able to choose a new way. For the first time in human existence, thanks to advancements like feminism and birth control, we can seek out ways of relating which are more just, equal, and free than ever before. There’s argument is empowering — in that it suggests we are sexual pioneers — but it’s also a weak one at the same time. Mainstream relationship writers respond by arguing that it’s impossible to go against our essential natures, often citing what they claim to be universal failure in the group or alternative relationships of the 1960s’ and 1970s’ counterculture.

Sex At Dawn flips all of that around. Instead of being a state we evolved into, the modern monogamous marriage and culture negative toward free sexuality (especially that of women) are a modern aberration, brought into the lives of humans around the same time we invented agriculture. Like war, it is a byproduct of that technology, which allowed for an explosion in human population yet may have been one of the most damaging things we did to ourselves. It not only resulted in people becoming property, but also in famine and ill-health which we are only now beginning to fully overcome with medical technology.

The authors amass an impressive wealth of evidence to demolish the modern myth of monogamy, while giving us hints at what might have been before. In making their arguments, Ryan and Jethá draw from a wealth of fields: the behavior and anatomy of our closest primate relatives as compared with our own, accounts of the sexual behaviors of dozens of pre-agricultural human cultures, and even things like the shape of the penis or a woman’s “female copulatory vocalizations,” which they argue originally served to call other men to join in the fun. The book is witty and full of insightful observations, from criticisms of the methods of Jane Goodall or the anthropologists who studied the infamous Yanomamö to arguing in the footnotes that the hammock was the first human invention. Sex At Dawn is compelling and entertaining reading from start to finish.

Above I mentioned there was one notable exception to the inspiring view of human sexuality which this book creates for its reader. That exception is that this view is an extremely heteronormative one. I am not trying to argue that authors are actively homophobic. On the rare occasions it mentions queer people, Sex At Dawn handles this topic with sensitivity; a female-to-male transperson’s experiences is even cited as it relates to the effects of testosterone. However, nowhere do Jethá and Ryan speculate on where queer people fit into their image of pre-agricultural sex, or even if they existed at all. Even worse, the book cites the same studies which mainstream science journalists have used to make hyperbolic claims that “male bisexuality doesn’t exist!” While the authors never go that far, these studies fit their idea that women’s sexuality evolved to be extremely fluid even to the point of bisexuality while a man’s is rigid and unchangeable after a brief period in his teens.

After feeling so uplifted by the sense of normalcy I got from the rest of the book, this was quite disheartening for me. Of course, this book is in many ways a survey of existing science and anthropological study, placed into a new context. As backward as our view of alternative sexualities has been for so long, it’s not surprising that there may just not be a lot to go on when it comes to, for example, homosexuality or bisexuality among hunter-gatherers. Further, it seems like the authors intended the book primarily for those who have not yet begun to question mainstream, monogamous heterosexual relationships. Perhaps this merely means there is room for a followup book, perhaps titled Bisexuality At Dawn or The Queers of Prehistory.

For all that it bothered me not to find my queer behavior depicted in the pages of this book, it remained an enlightening and thought-provoking read. Sex At Dawn makes a powerful argument that the conventional monogamous marriage is ill-suited to human nature. Far from being a result of a poor morals, genetic mutations, or a modern feminist invention, the breakdown and questioning of the “conventional” nuclear family may actually be because evolution itself made us poor candidates for a modern convention that is the product of a repressive society. Wisely, the authors make not attempt to tell us what to do with this knowledge, leaving it up to us to integrate it into our lives. Its conclusions and the questions they raise will shake up those who haven’t begun to re-examine societal norms, just as much as it can inspire those who have.

If you enjoyed this review, check out more of my writing or follow me on Twitter.

Disclaimer: I was not paid for this review, but the publisher sent me a free copy of the book in return for my honest opinion. For more information, visit the Sex At Dawn homepage.